“I come now to treat a very delicate and difficult subject–the unfortunate marriage of Mrs. Willard with Dr. Yates. Gladly would I omit this chapter, but, by so doing, this memoir would be partial and incomplete. It is misfortune, not folly, which I am about to describe; and, when viewed in all its relations, reflects no discredit on Mrs. Willard…” -John Lord Life of Emma Willard (1873)

“The common school should not longer be regarded as common, because it is cheap, inferior, and only attended by the poor and those who are indifferent to the education of their children, but common as the light and the air because it’s blessings are open to all and enjoyed by all. That day will come. For me, I mean to enjoy the satisfaction of the labor…” -Henry Barnard

Definitions:

Common School: Public School

Normal School: A school that taught teachers how to teach

School Society: School System or Board of Education

School Visitors: Inspectors

Education was always very important to the Moore family. In the early 1800’s Connecticut towns began forming school societies, and in 1810 Connecticut started a school fund for the societies to help pay for their schools, teachers, textbooks, etc. By 1826, there were 208 school societies, which included Berlin, with 24,851 students statewide between the ages of four and sixteen. By 1829, there were 84,899 students. In 1826, Sheldon Moore’s brother, Oliver was one of three elected committee members on Berlin’s first school society, which was formed in Kensington. In 1829, Sheldon was named Moderator, Oliver was Clerk, and another brother, Eli was hired as a teacher. Later Sheldon would become a school visitor.

However, by 1835 an investigation initiated by Governor Henry Edwards found that Connecticut schoolhouses were poorly furnished, parents had become indifferent, teachers were unskilled (most were woefully underpaid) and attendance was down by more than six thousand. The state’s common schools were in need of an overhaul.

Enter Henry Barnard. Yes, the Henry Barnard. But, he wasn’t yet the Henry Barnard we know today. The future education reformer and the country’s first Secretary of Education was at the time only eight years removed from graduating Yale. He was currently spearheading a project to revive the long dormant Connecticut Historical Society and had founded the Hartford Young Men’s Institute, or as we know it today, the Hartford Public Library. More importantly to this story, in 1837 he had been elected as a Legislator in the Connecticut General Assembly. He was the youngest representative ever elected by Hartford voters at the time.

He also began publishing (sometimes at his own expense) the Connecticut Common School Journal. The periodical was published from 1838-1842 and offered some transparency into what Barnard was trying to accomplish (better and more comfortable schoolhouses, improved teaching methods, etc.). Reports from school societies and school visitors also appeared in every edition. Through Barnard’s unrelenting efforts, a real interest and excitement began to take place around the common schools.

Note: In Commentaries on American Law (1844), James Kent called the Connecticut Common School Journal, “a digest of the fullest and most valuable information that is to be obtained on the subject of common schools both in Europe and the United States.”

Barnard believed that women made better teachers and began to eliminate all but the best male teachers. He wrote in the Common School Journal, “Heaven has plainly appointed females as the natural instructors of children…”. Furthermore, he believed women should also be running the schools as principals and superintendents, writing, “Experiments as far as they have gone, encourage the belief that well-educated females may bear a far more extensive and important part in the instruction and government of our common schools…”. What he could really use to prove his theory was an extraordinary female teacher. Preferably one who had experience running a school.

Enter Emma Willard. Yes, the Emma Willard, a native of Berlin (Kensington actually) who, by 1838, had already made a name for herself as an author of textbooks and had cofounded, with her late husband John Willard, the very successful Troy Female Seminary school in Troy, New York. She had also amassed quite a bit of money. On September 17th of that year, the widow Mrs. Willard married Dr. Christopher C. Yates of Albany, New York (also widowed, and like her first husband, older than herself). The ceremony and reception were held at Emma Willard’s beloved school, surrounded by one hundred and fifty of “her girls”, who were all dressed in white and held white flowers. Following the celebration, the couple honeymooned at Niagara Falls. Emma had recently relinquished control of the seminary to her son, John and his wife, Lucretia, who became superintendent and principal respectively. Dr. and Mrs. Yates were now ready to begin their new life in Boston, where Emma had rented a house.

But only nine months later, the couple was separated. Emma had walked out on her husband. The decision to so was not be taken lightly by a woman in the 19th century. A wife who abandoned her husband risked losing everything and could become a social pariah. However, Emma’s marriage to Dr. Yates had become so intolerable that she felt she had no other choice. In a letter to a close friend, she later explained why she left and described Yates as a man who was far different from the man she had married:

“Words cannot tell of the agonies I have endured. He found my fame and my own opinion of possessing talent above the common mind inconvenient to him, and he set himself systematically to work to bend and break my spirit. This was not the worst. His shocking irreligion, manifested at times when he acted as a priest in the family, to lead in such devotional services as we kept till the day I left him, gave me more anguish than anything else, and were a nature to justify me, before God and man, in refusing to live with him.”

Besides his feeling threatened by her intellect and mocking her religion, there was a whole money issue. Despite a marriage contract, that she had drawn up before their marriage to protect her assets, which were considerably more than his, he had found ways to access her accounts (possibly by forging her name or that of her son, as he was later accused) so that he, and his children could live lavishly. This began the night of the wedding, when he was given the bill for the reception dinner and he subsequently handed it to her. Later, when they moved into their house (that she rented), he spent $5000 of her money to furnish it. When he informed her that he wanted her to buy a mansion, she finally put her foot down and told him no, and it was then that he set out to break her.

In June 1839, Emma and Dr. Yates left Boston together. He was going to visit his children in Nova Scotia, and she was going to Troy. They went as far as Providence, Rhode Island and parted ways. She didn’t tell him she was leaving him because she was still unsure that she was going to, and he was unaware that she was unhappy.

Once in Troy she decided that she could no longer live with this insufferable tyrant, and with her son, she drafted a letter that she sent to Yates for him to sign, that she hoped would dissolve the marriage. He didn’t sign it. Instead, the jilted husband made a copy of it that he later shared with the Boston Globe. Throughout 1839 their separation would be played out in the newspapers around the country, with the papers first leaning towards Willard and later towards Yates.

An article that appeared in the Hartford Patriot in August, and was widely circulated, gave Mrs. Willard’s account of the matter and called Yates a “tyrannical and unprincipled man, and withal an open infidel and debauchee”. It went on to say that the doctor had refused to let Emma remove her furniture or her carriage from their home and she had hired a lawyer (her brother-in-law, John Phelps) to retrieve her property.

Upon his return from Nova Scotia, Yates angrily wrote to the Boston Globe concerning the “libelous attack” upon him in the Patriot and the New York Sun and promised he would be visiting Hartford and New York to demand his “due acknowledgements” from the publishers of both newspapers. Yates also defended himself, stating he had never taken money from Emma Willard, and the reason for her departure was that she had asked him to lend his name to a seminary school that she intended to open in Boston, but he had refused because he was planning on them moving to Albany, so that he could resume his practice. The threat of libel had the result he had intended and many of the papers that had run the Patriot article, now ran the Globe article. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote, “How long has Mrs. Willard been a disciple of (feminist) Fanny Wright? Or in what school can she have learned that differences of opinion justify a wife in abandoning (her husband)”?

Besides the bad press, which is something Emma Willard not have been used to, upon her arrival in Troy she had asked for control of her school back, and the Board of Directors had denied her request. They were quite satisfied with the work that John and Lucretia Willard were doing. With that, she decided to return home. To Connecticut that is, and her hometown of Berlin. In her native state her reputation was still beyond reproach, and it was there that she filed for a divorce. However, divorce cases were heard before the state legislature, which met annually in Hartford for a few weeks in May. It might take years before her case came up. She moved in with her sister, Mrs. Mary Lee, in Kensington and prepared for a long wait.

In the winter of 1839, Henry Barnard visited Kensington to lecture before the school society. Mr. Barnard and Mrs. Willard were familiar with one another, having been introduced years earlier by a mutual friend, Dr. Eli Todd. It was at this time that Barnard asked Emma if she would write a proposal on how to improve the common schools in the town. Wishing to be useful and keep herself busy, she agreed.

On Wednesday, March 18, 1840, a “great meeting” about the common schools was held in Kensington at the Congregational Church. Even though it was held in the evening and the snow on the ground was very deep, the meeting house quickly filled up with not just the residents of Berlin, but many of the surrounding towns as well. The Reverend Royal Robbins quipped that in his 22 years as pastor he had never seen the church so full. Robbins was in attendance, not just because it was his church, but also because he was a school visitor in the society. The children from the parish’s four schools, who had been standing in line on the steps outside the front doors under the banners while a hymn, written for the occasion by the good reverend, were then lead in and addressed by Jesse Olney of Southington. Music was played by a band from the Worthington parish, and then Emma Willard’s address and proposal were read aloud by Elihu Burritt (the “Learned Blacksmith” as he was known) of New Britain. Please remember that in the 19th century it was still not proper for a woman to speak publicly. The crowd listened to her words, “with deep and thrilling interest.” Then refreshments were served, and the children were led out as they had come in. The night had been a huge success.

Emma Willard’s proposal caused a great deal of excitement among the people of Kensington. The school society was very impressed and immediately asked her to be superintendent of the schools for the upcoming summer session. Although she considered the position beneath her, she agreed, but only if she could get the full cooperation of the parents of Kensington. She did.

She wrote to Henry Barnard on May 17th to say she had accepted the position and to outline the upcoming changes to the schools. As he wished, all four of the school’s teachers would be female. The one large classroom in each of the schools would be subdivided into separate rooms and children would be taught in classrooms with children of their own age. Older girls who excelled in their studies would be asked to be teacher’s assistants, who would be trained to become teachers. This being the only way to train teachers given her resources, and in fact, the way Mrs. Willard herself had been trained in 1804 at a school in Berlin (Worthington to be precise). She had also tested this method, with great success, in Troy.

Upon examination of the school’s libraries, she found they contained too much fiction, which she believed was detrimental to the children’s minds, because young scholars may not be able to distinguish the difference between fact and fiction. Therefore, she recommended removing most of the fiction from the schools.

Among her other proposals was this:

“Each schoolhouse should, we think, be provided with a clock; no matter how plain, if it do but perform its office correctly. Whatever is to be done regularly requires a set time as well as fixed place, and teachers on low wages cannot afford to buy watches…”

(Did Emma Willard invent the school clock?)

As superintendent she drilled her teachers constantly. Even requiring them to come in on Saturdays for further instruction and testing while the children were away. She interacted with the students, sometimes teaching them herself. She composed and taught them a song called Good Old Kensington, that they sang together everyday. Music was part of an expanded curriculum that well beyond “reading, writing and ‘rithmetic”, and now included geography, history and scripture. Girls were taught the “use of needle and thread”, which they would need in their “feminine employment” (Mrs. Willard, though she believed girls and boys should be taught equally, realized that most girls would go on to become wives and mothers, and should be taught the necessary skills in school. At the Troy Seminary, she has been credited with first introducing Home Economics).

In a report to Henry Barnard published in the November 1840 edition of the Common School Journal, the visitors, that included Sheldon Moore and Royal Robbins, had nothing but praise for Willard’s improvements, and noted, “It is believed that the public opinion has been decidedly favorable, and that the parish has acquired a reputation abroad which it should be anxious to sustain.”

Also that fall, Mrs. Willard organized the Female Association to Improve Schools in Kensington’s east district school (Sallie Caliandri of the Berlin Historical Society, believes this may have been Ledge school, and the other three were possibly West Lane, Stockings Corner and Blue Hills). Every mother in the district, with children in school, and two single women joined the association. This was one of two schoolhouses that had been remodeled per Willard’s proposal, and one of the association’s objectives was to improve the appearance and overall comfort of the school.

However, by the time the association began meeting Emma had been called away to Hartford by Henry Barnard for a new project, the formation of a State Normal School. Barnard wrote in the Journal in January 1841, “The great and pressing want, that in comparison with which most of the others sinks into insignificance, is the want of well qualified teachers…It is apparent then, that the normal schools are imperiously called for by the wants of the common schools as they now exist, and are still more essential in view of the great improvements which the system is destined to receive.” Normal schools had existed in the United States since 1823, when the first was built in Concord, New Hampshire. The first State Normal School had just recently opened in 1839 in Lexington, Massachusetts, through the efforts of Horace Mann, another education reformer and personal friend of Barnard. If Barnard could get the legislature to approve his proposal, Connecticut would have the second state-run normal school in the country.

His plan was to have Emma run the school, and one of the first questions, the reason she had been called to Hartford and put on a committee, was where in the state would the school be located? The decision would ultimately be hers.

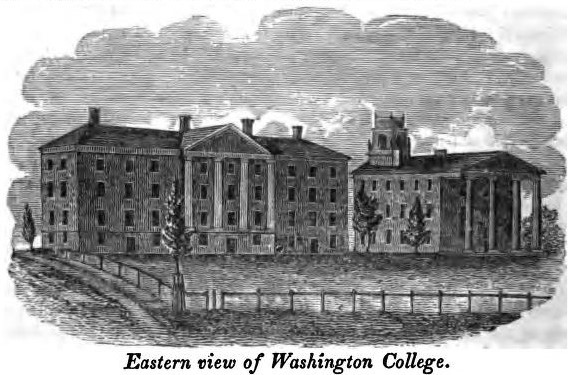

The first and possibly most obvious choice was Hartford. In fact, there was a large brick building available in the southwest part of the city, near Washington College (Trinity College today), that Emma believed would be perfect. A small portion of the building was an orphanage, and the children would be in her care. The orphans would then be taught by the teachers in training from the normal school without, as she wrote, “a set of unreasonable parents to break up our plans”. By early February 1841, she seemed convinced that the school should be there. But, there had been a second choice. Kensington.

Yes, Kensington! Just when she thought she had made up her mind she received a petition from Kensington which was signed by nearly all the citizens of the parish. The children even sent her letters asking her to come live among them. Sheldon Moore also wrote her; however, he had been ill that winter and his letter to Emma had been delayed until he felt better. On February 20th, she wrote him from Hartford to say that though a final decision hadn’t been made, she wished she had heard from him earlier, and if she had, she would have already chosen Kensington. She was pleased to hear of the “good spirit” that “exists in Kensington” and told him, “You are certainly right in supposing that other things being equal, I would rather be the means of benefitting my native place than any other.” Emma was now clearly conflicted and wrote her daughter-in-law on March 2nd and said, “I cannot help thinking that I should be happier there (Kensington) than in Hartford.

But where to locate a normal school would be a moot point if the state legislature didn’t approve Barnard’s proposal, and that decision, like Emma’s divorce. was going to have to wait.

Meanwhile Mrs. Willard’s common school improvements and her Female Association were both successful. In May 1842, Reverend Robbins reported on his visit to the east district school, which was later published in the Common School Journal. He wrote that trees had been planted for shade and bushes and flowers now adorned the outside of the school. Inside, there were new, more comfortable desks and chairs, a place for the children’s hats, bonnets and coats, a globe, maps and a model of the solar system. There was also a clock, but it wasn’t working (seriously?). Robbins reported that the association met once a month at the school and if school was in session, then the children would be invited to attend the meetings. He noted that, “The effects of these meetings on the school is visible”. In fact, in over twenty years as a school visitor, he had never seen children more willing and ready to attend school and eager to learn, and he hoped that the results he witnessed would carry on for generations to come.

However that same year, the normal school project suffered a blow when a new governor and legislature were elected and the Board of Commissioners for Common Schools was subsequently abolished. Now disenchanted with politics, Henry Barnard didn’t seek another term as the Whig representative for Hartford. He would never again run for office and instead turned all his efforts to the betterment of education in the United States, and would soon leave Connecticut for Rhode Island to improve the common schools in that state.

Finally, in May of 1843, the state legislature heard a Petition of Benjamin Allyn and others for a Normal School in Berlin. Mr. Allyn, Esq. was a Kensington resident and a nearby neighbor of Sheldon Moore. After the petition was read, it was referred to the Committee on Education where, without Henry Barnard’s support, it died a natural death.

But, there was good news later that month when the legislature granted Mrs. Emma Yates a divorce, and as she had requested, allowed her to go back to her first married name, Emma Willard. This being the name she preferred, and the name she had been using since her separation from Yates.

Her exile in Kensington now over, Emma contemplated moving to Philadelphia, where she had been asked to help improve their common schools. She also toyed with the idea of publishing her own common school journal in that city. This time however, her son and daughter-in-law intervened and convinced her to return to Troy, where they felt she belonged.

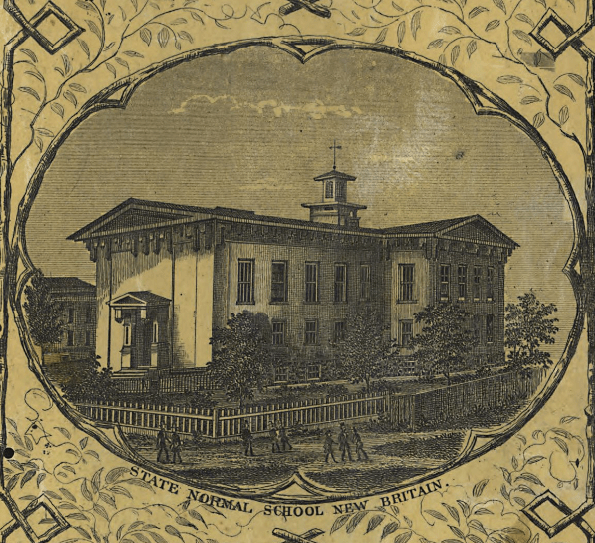

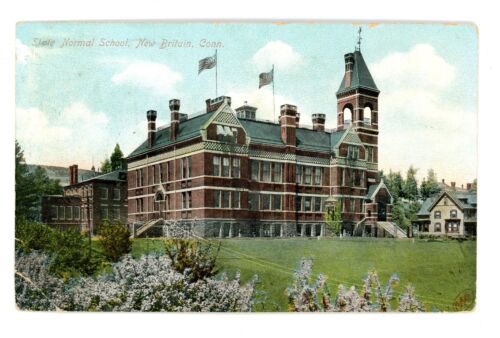

It took six years, but in 1849, the legislature finally passed an act to establish a State Normal School. The school would not be built in Hartford or Kensington. Instead, it was established in New Britain on May 15, 1850. The following year, a new building, that would become the new school, was dedicated in that city, on Main Street where it intersects with Walnut and Arch Streets (the building is now gone). In attendance that day was Henry Barnard, who was back from Rhode Island and was once again Superintendent of the Common Schools in Connecticut and had been named principal of the normal school. The school still ended up being the second state-run normal school in the country.

In 1883, the normal school moved into a larger, grander building. It was moved once again in 1924 and renamed the Teacher’s College of Connecticut. Today it is Central Connecticut State University (CCSU. Go Blue Devils!) If one were to visit the impressive campus, they would find Henry Barnard Hall, the Elihu Burritt Library and the Emma Hart Willard Hall and parking garage.

As for Dr. Christopher C. Yates, he died in Nova Scotia on September 23, 1848. Though Emma Willard’s divorce from Yates never really tarnished her legacy, his reputation may have always been questionable. In a biographical sketch that appeared in the Annals of the Medical Society of the County of Albany after his death, Dr. Yates’ many accomplishments are listed, but the sketch ends with this comment about his personality:

“…in his character and example, there was nothing to admire, but everything to avoid; and that his influence upon his profession, and upon society, was demoralizing.”

Sources:

The Life of Emma Willard by John Lord (1873)

Emma Willard, Pioneer Educator of American Women by Alma Lutz (1964)

Life of Henry Barnard, The First United States Commissioner of Education by Bernard C. Steiner (1919)

A History of Connecticut by George L. Clark (1914)

Connecticut Common School Journal (1838-1842)

The Connecticut Quarterly an Illustrated Magazine, Vol. IV by George C. Atwell (1898). Picture of Henry Barnard

The Connecticut Magazine an Illustrated Monthly, Vol. VI by George C. Atwell (1900). Picture of normal school, circa 1900 and Elihu Burritt

Smith’s Map of Hartford County, Connecticut H. & C.T. Smith (1855). Location of normal school and picture, circa 1855

Emma Willard letter, 1841, February 20 David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library (call number Sec. A 173). Letter can viewed online at Duke University digital collections website:

Old Sturbridge Village Research Library, Oliver Moore Collection (items 1974.1.1.2.6 and 1974.1.1.2.11, Berlin, CT school society minutes)

Numerous newspaper articles available on newspapers.com

I would like to thank the Berlin Historical Society for their support. https://www.facebook.com/berlincthistorical/